Aside — Wherton and England

This alternative England could only be viewed through a peculiar window from the real one. Episode 1 of The Tripods[1] was broadcast for the first and only time on 15 September 1984 (that’s 1984 AD, of course) — a Saturday, at 5:15 pm.

And for once, we might think about the surround to this image: all of the extraneous stuff — reality — which has been cropped away from this screen-shot. What sort of mood, what frame of mind, were the viewers in?

It was still full daylight on a dry, cool autumn afternoon — though when episode 13 ended, three months later, it would be night outside. A little over 1 in 6 of the British population were watching the premiere, and that now seems a lot, but was only modestly good then. It seems unlikely that the Prince and Princess of Wales tuned in, since their second son was being born that same day: and so a Henry joined a William, though they were Windsors and not Parkers.

Television is forever both old and new. Through constant reinvention, it has somehow remained at the leading edge of consumer technology for nearly a century now, never settling into an essentially final feature set, like the radio or the washing machine. That was as true in 1984 as today. Most British homes had traded up to a colour model during the 1970s, though smaller sets, often in children’s bedrooms or kitchens, remained black and white. (Here’s an eye-opening page from the Argos catalogue for that autumn.) Changing channel had become a push-button process without a ten-second delay, and there was even a whole new channel to watch, the first since 1964: Channel 4, which went on air in 1982. Teletext — on-screen programme information, news and sometimes subtitles — had begun experimental transmissions as early as 1973, and went mainstream in 1981. By September 1984, every recent set could display news and programme information in primary-coloured text. Episode 1 of The Tripods was thus announced as:

Science-fiction adventure in which two teenagers are caught up in a battle to free the Earth from alien control.

These newer sets no longer looked like furniture, but only because wood-effect cabinets had been replaced with grey plastic. A typical screen size was 25 inches, and behind the image was a glass cathode ray tube, housed in metal shielding, and cabled to antennas on the roof of the house. It was a solid-looking box which ran at high voltages, was not at all safe to open, and needed two men to carry. Colour and brightness were muted by modern standards, and so the source material had to be fairly saturated to compensate. Flatter and lighter screens were coming in, but even so the curvature of the glass distorted the fringes of the picture. The dream of a perfectly rectangular image was still some way off, but progress was impressive all the same. Most astonishing of all was the video recorder, which made it possible to capture programmes for the first time — though never quite at broadcast quality, and with playback which sometimes wobbled. Since blank 3-hour tapes still cost around £5 each in autumn 1984 (£16 in 2024 money), they were used more for time-shifting than as an archive. Besides, they were bulky. Many people will have recorded The Tripods to watch later, but almost all will have recorded over it again.

The world was led by Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, Helmut Kohl, François Mitterand, and Konstantin Chernenko. This was not always a reassuring group, and historians now think the 1983 NATO exercise might conceivably have ended in a nuclear exchange and, for all practical purposes, the end of the world. Certainly the prospect of a hydrogen bomb destroying Sheffield looked all too real in the TV play Threads,[2] which broadcast only a week after The Tripods. But, as with climate change today, people had been worrying about nuclear armageddon for so many years that it had lost all sense of urgency.

Culture seemed upbeat and bursting with life. Bruce Springsteen released Born in the USA, Prince released Purple Rain, and Michael Jackson’s Thriller continued its endless charting run.

Wham!, Phil Collins, Marillion, and Frankie Goes To Hollywood were all major British acts in 1984: U2 was on its way up, Duran Duran on its way down. Grandiose 1970s bands like Yes, Rush and Genesis were having a resurgence as they adopted more modern instruments.

Dire Straits’s album Love Over Gold and the ECM recording of Arvo Pärt’s minimalist composition Tabula Rasa were showcases for a new compact disc format, which exploded in popularity in the run-up to Christmas.

Though the Oscars would go to Amadeus and A Passage to India, the crowd-pleasing movies were Ghostbusters, Beverly Hills Cop, and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. In a top ten dominated by comedy crossovers, only number nine could be called science fiction — and that was Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, which was more nostalgia than anything else. Sci-fi had not of course come to an end, but movies like Tron and Blade Runner, both 1982, and William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer, suggested a new turn to a more inner space.

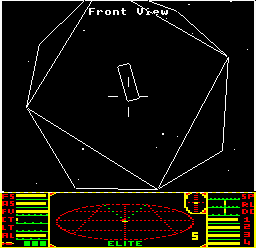

If science fiction had moved on from dreams about spaceships, perhaps it was because that future had arrived. The Space Shuttle programme was at its maximum point of bravado. In November, it carried off a salvage operation in which free-flying astronauts in jetpacks captured a pair of rogue satellites. More people have walked on the moon than have flown free in orbit, but it only barely made the news, and then as a comedy item, the joke being that the Shuttle was now a repair truck. (The BBC’s short-lived series Star Cops, 1987,[3] was based in this same so-called High Frontier milieu, and by the same token wasn’t met with wonderment.) Home computers were a reality, too, which undercut the sinister behemoths of older movies, like Colossus or HAL 9000. Indeed, computers had so much penetrated British daily life that they were now a third force, after television and Hollywood, vying for time on the TV set. Elite, the BBC Micro open-world trading game, was released on 20 September, just five days after the debut of The Tripods. Two undergraduates working on their own had made what turned out to be a bigger splash in British culture than any television drama of its time.

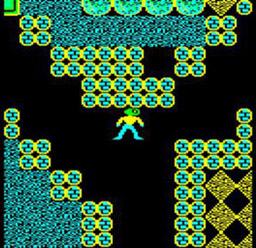

Ant Attack (1983), Jet Set Willy (1984), Repton (1985), and many others, brought further imaginary worlds into British life. These often rehashed old tropes of genre fiction — spaceships, dragons, ghosts, mazes, pyramids — but they also turned “the computer” into a domestic appliance, which you could buy from the Argos Store or from Boot’s the Chemist, like a kettle or a sandwich toaster. We lived in an age of wonders, and it all felt quite normal at the time.

Despite all this consumerism, the British cultural mood of the late 1970s — societal pessimism, and a nostalgia for bygone days — had never really gone away. There had been a particular longing for a pre-mechanised, rural England in the years up to 1980. CAMRA, the Campaign for Real Ale, founded 1971, had grown as fast as any pressure group. Laura Ashley (1925-85) had brought her period clothing business to great commercial success on the high street. The Country Diary of an Edwardian Lady (1906) became a publishing juggernaut after its 1977 reproduction edition. It is perhaps telling that the BBC show Wings (also 1977),[4] in which a young blacksmith joins the Royal Flying Corps at the outbreak of World War I, devotes almost as much screen time to the life of Becket’s Hill, the Sussex village he has left behind. We learn as much about farriers and the forge, silent-movie cinemas, and how to woo a widow as about the B.E.2c biplane. A potent myth of golden summers past, when everything was more secure, lives on in such shows. The Onedin Line (1971-80)[5] took it as axiomatic that sailing clippers are right and steamships wrong. Even the polishing, dusting and scrubbing done by the servant classes in Upstairs, Downstairs (1971-75)[6] is somehow artisanal, since it is all done by hand, before the hoover and the dishwasher and shop-bought solvents commoditised housework.

But if television looked to the past for comfort, the other side of that coin was to doubt the future. Speculative programmes began to think about systemic collapse, as they often do during times of turbulence. In Britain the 1970s had seen a series of economic calamities interrupted by fitful lulls, and numerous alternate histories were made as dramas, all of them showing a pivot to fascism: The Guardians (1971),[7] State of Emergency (1975),[8] or An Englishman’s Castle (1978),[9] for example. Programmes as different as Survivors (1975-77),[10] which wipes out most of the human race with a plague, and the lecture series Connections (1978),[11] a popular history of science, contemplated an even more extreme reset of society: a forcible return to the plough. Quite an adjustment, such shows concede, but would it be so very bad to have to make all our own candles and butter at the kitchen table? Even the sitcom The Good Life (1975-78),[12] in which Tom and Barbara Good convert their Surbiton house into a small-holding, was at some level a dream of simplicity closer to the land. Tom Good gave up “the rat race” (a phrase often used in 70s television) voluntarily, as did Charles, one of the leaders in Survivors, who turns out to have been “a self-sufficiency nut” (another phrase of the times) before the plague. Charles’s common-law wife, Pet, perceptively remarks how much more he enjoys life after the apocalypse. The total ruin of society has given him purpose, and even a sort of vindication.

In the spring of 1984 unemployment in England reached 11.9%, still a record. The smoke-blackened factories, uncompetitive steel-mills and idle shipyards of Manchester, Glasgow and Belfast seemed to belong to a different country entirely from the financial economy booming in London. Over the summer, the largest strike since 1926 had led to violence seldom seen in mainland Britain. For every contented family in Maidenhead or Sevenoaks, another was miserable in Consett or Corby. Yet something which did unite them is that all had television sets. Little wonder that dramas evoking a horse-drawn world offered escape — from strife, from metric units, decimal currency, processed food, free trade, inflation, and all of the rest: above all, from pessimism and complexity. Why not let the small screen be a refuge, back into a happy past that never was? The contented world of Wherton, filmed with a notably sympathetic camera-gaze in episode 1 of The Tripods, offers that temptation in its purest form. All the same, and in marked contrast to anodyne shows like All Creatures Great and Small (1978-90),[13] whose Yorkshire Dales were a whimsical Eden, The Tripods is not about Paradise but about what is wrong with it. Episode 1 showed us happiness, but also Vagrants — the 11.9% of Wherton, so to speak — and authority figures who insist that everything is as it should be. Wherton is England.

Television cited:

- The Tripods (BBC, 25 × 25 minutes, 1984-85), produced by Richard Bates. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- Threads (BBC, 1 × 112 minutes, 1984), by Barry Hines. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- Star Cops (BBC, 9 × 50 minutes, 1975), produced by Evgeny Gridneff. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- Wings (BBC, 25 × 50 minutes, 1977-78), produced by Barry Thomas. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- The Onedin Line (BBC, 91 × 50 minutes, 1971-80), produced by Cyril Abraham. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- Upstairs, Downstairs (London Weekend Television, 68 × 50 minutes, 1971-75), produced by Alfred Shaughnessy. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- The Guardians (London Weekend Television, 13 × 50 minutes, 1971), produced by Andrew Brown. IMDB.

- State of Emergency (BBC, 3 × 50 minutes, 1975), by John Gould. IMDB.

- An Englishman’s Castle (BBC, 3 × 50 minutes, 1978), by Philip Mackie. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- Survivors (BBC, 38 × 50 minutes, 1975-77), produced by Terence Dudley. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- Connections (BBC, 10 × 50 minutes, 1978), produced by James Burke. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- The Good Life (BBC, 30 × 30 minutes, 1975-77), produced by John Howard Davies. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- All Creatures Great and Small (London Weekend Television, 90 × 50 minutes, 1978-90), produced by Bill Sellars. Wikipedia; IMDB.

Next: Aside — The Big-Top Gala ● Prev: Episode 1