Aside — Not Easy to Follow

That makes two ways in which The Tripods[1] did not exist in isolation: it was made in the mid-1980s, and it was made for Saturday afternoons by BBC1. Its deeper context was that it was made from a trilogy of children’s books: The White Mountains,[2] The City of Gold and Lead,[3] and The Pool of Fire,[4], by John Christopher: short books in effect forming a single narrative written in 1967-68.

These were titles found in any school or village library. Partly through the cheap-paperbacks boom of the 1970s, partly through an increased willingness of newspapers like the Guardian or the Times Educational Supplement to review them, and partly through a symbiotic relationship with children’s television, children’s books were having a moment. These particular titles were easy enough for librarians to approve of. They were adventure stories without controversial content, told directly, and in much the same spare, grammatical English of adult novels of the time. The narrator seemed older than his years, reflecting on his experiences with some psychological depth. John Christopher is often called a science fiction writer, because he had made his name with a series of catastrophic novels in the mode of John Wyndham, The Death of Grass[5] being the best remembered. In fact he wrote in a number of genres: his output, now being somewhat rediscovered, included astringent romances, supernatural-happening novels, and survival thrillers. By 1967 he was a decently-regarded adult writer, known to every librarian, when he unexpectedly switched to children’s fiction in mid-career. It was absolutely the remaking of him. The opening paragraph of The White Mountains, his debut as a writer for children, is a fair sample of the style throughout the Tripods books:

Apart from the one in the church tower, there were five clocks in the village that kept reasonable time and my father owned one of them. It stood on the mantelpiece in the parlor, and every night before he went to bed he took the key from a vase and wound it up. Once a year the clockman came from Winchester, on an old jogging packhorse, to clean and oil it and put it right. Afterward he would drink camomile tea with my mother and tell her the news of the city and what he had heard in the villages through which he had passed. My father, if he was not busy milling, would stalk out at this time with some contemptuous remark about gossip; but later, in the evening, I would hear my mother passing the stories on to him. He did not show much enthusiasm, but he listened to them.

Of this paragraph, only the clock makes it into episode 1. The vocabulary is all within range of an older child, but the compression of time is unusual for a children’s book. Dialogue is often reported, not spelled out. This single paragraph could easily have been a whole chapter, in that it introduces the narrator’s family — they’re well-off tradesmen, father is brusque and stand-offish, mother more conciliatory — yet is also about the village, its technology, and its horizons. Mrs Parker drinks camomile tea, not Earl Grey, which would have to come to England from India.

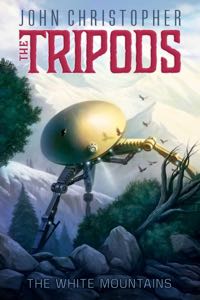

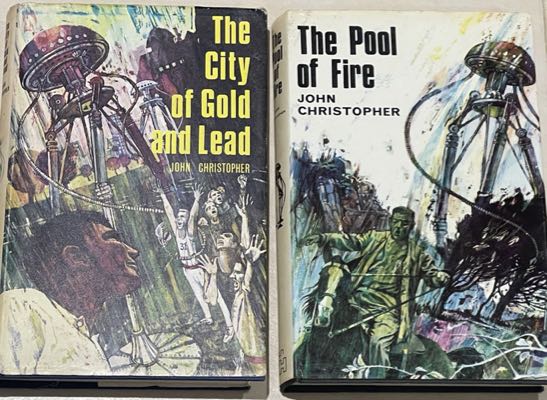

Any book published fifty-seven years ago which has never been out of print is by definition a classic. Literally dozens of cover artists have had to decide what the Tripods look like (spiders, crabs, jellyfish, trucks?), and how old the boys are (short trousers, or long?). If nothing else, a bare sample of their very different decisions shows the range of visual adaptations which could be made:

Tim Hildebrandt’s appealing 1990 covers, in the style of idealised American landscape paintings, had a long life among the US editions, but otherwise these designs have seldom lasted, and so they don’t really establish a clear picture of the books — in the way that, say, the Paget illustrations for Sherlock Holmes make it hard for us to see him any other way. Still, if there’s one edition which original viewers of the show might have seen, it would be the early 1970s Hamish Hamilton library hardbacks, with their distinctive Tripod spines. These are notable for pushing the “boys” well into their twenties, if not older: the Will Parker on the cover of The Pool of Fire could be the hero of a Desmond Bagley or Alastair Maclean thriller.

So, the books had done well, and it would have been a reasonable bet in 1970 that by, say, 1975, somebody would have televised them. As can happen with adaptations, though, The Tripods spent some years waiting to be green-lit, and by 1984 it was a little out of its time. The books had been written for children whose toys had been mechanical and who played outdoors, in parks and woods and by canals. The show was broadcast to children who played computer games indoors. And yet, if 1984 was too late, it was also too soon. The Box of Delights, dramatised that same autumn,[6] drew from a book fifty years old, and half-remembered by adults of all ages. In contrast, nobody much over twenty would have read The White Mountains by 1984. David Lynch’s ill-fated adaptation of Dune,[7] on release at the same time as The Tripods was broadcasting, ran into a similar problem, with most movie-goers caring little for the need to follow a 1965 original. Later tries at Dune (2000, 2003, 2021, 2024) met with an audience steadily more respectful of the idea that faithfulness to a “classic” counted for something.

Such is the hazard of adaptations. They divide their audience into two tribes: those who know the books and those who don’t. The makers inevitably fall into the first tribe, the viewers mostly into the second. Consider, for example, just the cold open to episode 1 of The Tripods. If you remembered the books, you’d be struck by the clearly mechanical, not organic, Tripods on television, held in the air by everyday physics rather than some anti-gravity device. Many if not most of the book jackets for The White Mountains over the years had painted Tripods as being up on stilts, or else as hemispheres almost drooping tendril-like legs, more jellyfish than machine.

The Cap will seem more golden and foil-like on television than the heavy dark-metal mesh of the books. But if you had never read the books, none of that would mean anything to you, and you would instead be thinking what an unlikely hypothesis it all seemed.

The up side of adaptations is their richness and self-belief. They show us a fully realised world which the generous running time of television can embellish further. There can also be something fruitful in the way that the adaptation and the original constantly diverge and come back together. The BBC show portrays a more complex society than the books do, in which differences between the free and the Capped are more nuanced. In the trilogy as written, Vagrants are described only briefly and only in Wherton: but on television, we’ll see three further groups of them. Television also subverts the simple formula that the Capped people are all against us and the un-Capped are all allies.

But the down side is that adaptation ties a script down. Fundamental narrative shapes are stubborn to change. Dune, for example, wasn’t originally written as a novel but as two serial stories, so its plot isn’t very novel-shaped. An over-busy start runs into a lengthy doldrums. Similarly, even the most imaginative reworking of The White Mountains can’t bring in the third lead character for just ages. And regarded as one long novel, the first half of the Tripods trilogy is a historical adventure with sci-fi elements thrown in, while the second half is a sci-fi adventure with historical elements thrown in. This is all very unhelpful for a script-writer wanting to televise it.

The Tripods is on the whole a straight, rather than free, adaptation. It follows the book where it can and deviates when it must. This is what makes differences and discrepancies interesting. In this reading, I often highlight those divergences, but not because I think either version is “correct”. Changes are interesting not to keep some sort of score-card of faithfulness but because teasing out the reason for them can tell us about the story, or its tellers.

Sometimes changes are just down to what worked on the day, especially on location. For example, the bridge out of Wherton seen at the end of episode 1 was a ford in the book, but it makes no difference. The Tomb is a more interesting switch. It provides a faintly magical cave-like space of wrought iron and cobwebs, and is nicely visual. But the book unambiguously describes a derelict electricity substation, to emphasise the fall of technology. Why drop that element? Almost certainly because children can’t be shown playing with mains electricity, not even in the far future, not even with all the electricity long drained. A book can flirt with the forbidden in a way which television, which is more regulated, can’t.

Another switch in episode 1 is that the indoctrination of the children is done through lessons from a schoolmaster, not sermons from a parson. Why? In order to avoid the sensitive question of what happened to the Church of England when the Tripods came. The book can simply avert its eye, but television would have to show if there is a Tripod on the altar, and if there are still crucifixes. It’s for the same reason that Doctor Who, so obsessed with meeting the C-list celebrities of history (H. G. Wells, George Stephenson, Nikola Tesla and such), never thinks to check in on Jesus. And so, even though literally the first thing we learn about Wherton in the book is that it has a church, in The Tripods, we only ever hear its bell, and we’re told in episode 11 that it is rung only for Capping. And yet even once this change has been made, a faint residue of religion remains. In the schoolroom scene, there’s a very prayer-like echo as the children dutifully chant “we thank the Tripods.”

The script has to deal with a myriad of issues like these. There are places where the books are unfilmable, or don’t stand up to close examination, or can’t be made to fit the format. Episode 1 is a case in point there, too. The series opener needs to get us from Capping Day to the departure from Wherton, in order to get the story properly under way. But the novel has a very much slower beginning, describing nearly two months of village life. So the script ingeniously merges what in the novel are three non-overlapping time periods in May and June — Jack’s Capping, the visit of Ozymandias, and Will’s departure — and squashes them into a depiction of just two days and one night in early July. Jack’s doubts about Capping are transferred to Will, just as the Watch, which plays such a symbolic role in the novel, is transferred from John to Ozymandias.

Adaptation means hard choices. As clever as that solution is, it eats up about a quarter of the novel to make only one out of the thirteen episodes. The character of Jack is much cut down, which makes his Capping less troubling. The conflict between Will and Henry, though we’re told that they “always fight”, is reconciled so patly that it barely figures. We also lose Will’s relationship with his difficult father John. Even the American comic-book adaptation, which ran in the scouting magazine Boy’s Life for one page every month in 1981-86, finds room for an unsubtle frame in which Will thinks, in a think-bubble: “I wish you weren’t so cold and distant.” The original novel is subtler about why John is hard on Will: the shameful secret of the Parkers is that John’s brother turned Vagrant.

I wondered if his fear was of something quite different, and much worse. As a boy he had had an elder brother who had turned Vagrant; this had never been spoken of in our house, but Jack had told me of it long ago. There were some who said that this kind of weakness ran in families […].

If there is one key “fact” missing from episode 1, that’s it, I think.

Behind every context is another context. The books were originals, not adapted from anything else, but what does original really mean? They drew not only on the common staples of children’s adventure stories, but also on key apocalyptic novels in the British science fiction tradition. In many ways, The White Mountains describes an alternative ending for The War of the Worlds (1895)[8] — a version in which the Martians defeat Earth and then preserve it in a late Victorian stasis. The Martian fighting machines were even referred to, though with a lower case “t”, as “tripods”:

A monstrous tripod, higher than many houses, striding over the young pine trees, and smashing them aside in its career; a walking engine of glittering metal, striding now across the heather; articulate ropes of steel dangling from it, and the clattering tumult of its passage mingling with the riot of the thunder.

Or consider The Day of the Triffids (1951),[9] the prototype for post-war apocalypse novels. When the heroes eventually reach a geographical bolthole (the Isle of Wight), this safe haven is never quite described, and instead the novel ends with a homily about the future. That is exactly how The White Mountains also ends, and their final sentences are almost interchangeable. Such novels are often eye-witness narratives posing as memoirs of a catastrophe written years later: The Kraken Wakes (1953),[10] for example. This trope arguably went right back to Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826),[11] but came to the fore with H. G. Wells. Chapter the First of In the Days of the Comet (1866)[12] begins:

I have set myself to write the story of the Great Change…

In The White Mountains, Will is just such a narrator, actively telling and sometimes commenting on his story, and writing years after the event. Of the six novels mentioned in this paragraph, all six are first-person narratives.

Despite its apparent modernity, this is a genre of science fiction born from the Romantic dream of a depopulated earth, an overgrowing of the fallen columns of civilisation by the wildness of nature. In The Day of the Triffids, when the working-class orator Coker surveys the depopulated, collapsing city which used to be London — a process much accelerated by the book: a city won’t actually fall down just because it’s unmaintained for a few months — his reaction is to quote Ozymandias (1818), the poem by Mary Shelley’s husband.[13] Coker quotes the self-same lines heard in episode 1 of The Tripods.

To conclude, then, the Tripods story is not an easy one to adapt. It requires almost everything important about the Tripods (whether they are living things, who made them, what they want) to be withheld right up to the mid-point of series two. It combines difficult visual demands, which forced the show to be bold, with a spare, introspective writing style, which left the show largely to create its own dialogue. And by being a first-person story, it needs almost every scene to be shown from the same point of view, which is why Will is more or less permanently on camera. The Tripods books were, in the end, a hard taskmaster. If you were drawing up the scenario for a science-fiction show from scratch, you wouldn’t choose to have any of these constraints.

Works cited:

- The Tripods (BBC, 25 × 25 minutes, 1984-85), produced by Richard Bates. Wikipedia; IMDB.

- The White Mountains (1967), by John Christopher. Wikipedia

- The City of Gold and Lead (1967), by John Christopher. Wikipedia

- The Pool of Fire (1968), by John Christopher. Wikipedia

- The Death of Grass (1956), by John Christopher. Wikipedia

- The Box of Delights (BBC, 6 × 30 minutes, 1984), produced by Paul Stone. Wikipedia; IMDB. See also Wikipedia on the John Masefield novel of 1935.

- Dune (1967), by Frank Herbert. Wikipedia.

- The War of the Worlds (1895), by H. G. Wells. Wikipedia

- The Day of the Triffids (1951), by John Wyndham. Wikipedia

- The Kraken Wakes (1953), by John Wyndham. Wikipedia

- The Last Man (1826), by Mary Shelley. Wikipedia

- In the Days of the Comet (1866), by H. G. Wells. Wikipedia

- Ozymandias (1818), by Percy Bysshe Shelley. Wikipedia

Next: Episode 2 ● Prev: Aside — The Big-Top Gala