Not Counting...

Elsewhere in this essay I’ve made “adaptation” sound like such a simple thing. A straight arrow from the original to the new thing, with all the influence going one way. And so it mostly was, but only mostly. For example, John Christopher wrote a Tripods prequel (When the Tripods Came), and in part as a response to the show and certain things said about it, such as Brian Aldiss’s remark in an interview that the Tripods didn’t even have infra-red, and couldn’t see in the dark. Christopher also took the opportunity of the BBC series and its publicity to touch up the prose of the original books in their tie-in editions. Notably, he rededicated one edition of The City of Gold and Lead to “Richard Bates, pour encourager”, that is, to his television producer.

But this chapter is about other incarnations of the Tripods story: not the novels, not the show. Exactly what qualifies as such an incarnation is a boundary line that’s hard to draw. Is this essay itself an “adaptation”, for example? I’m going to be old-fashioned and say no. How about the BBC’s The Cult of… The Tripods documentary, or other behind-the-scenes looks? Again no.

I was very tempted to include the many painted book covers, 1967 to the present, as being — somehow collectively — another form of the Tripods myth. A single painting — or, more usually, a set of three, one for each volume in the original trilogy — is not quite a story. On the other hand, making these wasn’t a mechanical process. The artists chose different plot moments to illustrate, and imagined them very differently. Cinematographers for any future movie, if there is one, are sure to look at book covers past when they make their choices, just as Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies were heavily indebted to past Tolkien-licenced calendars, posters and dust jackets. So maybe illustrations like this are, in a tenuous sense, also “adaptations”. Still, since I’ve already talked about book covers elsewhere, we can leave this one here.

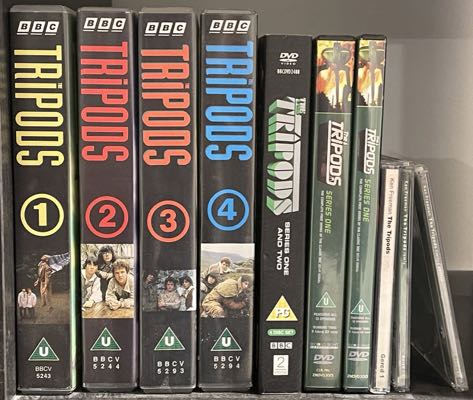

An even more tenuous case would be the various ways the show has been boxed up, wrapped, and made into an object. The Tripods began its second life on 5 April 1994, a few months shy of its tenth anniversary, when BBC Video unexpectedly released the first series uncut. This was spread across four instalments on VHS tape — episode 4, for example, opens cassette number 2-with-a-circle-round. The four boxes gave the wrapper of the programme a fresh visual design for the bookcase. All title sequences were preserved, though episode numbers were superimposed above the date-lines. (These numbers were later removed again, and so can’t be seen on the second and thus far final round of DVDs.) The soundtrack too was released, remastered and reimagined in the 1990s.

Though these reframings are not without creativity — the logos, the graphic design, the menu screens — they cannot really be called “adaptations” in any useful way. Nor can the whole range of secondary, promotional forms of The Tripods made to publicise the show in 1984. Penguin brought out tie-in editions of the books with publicity stills on the cover. The programme’s theme music, somewhat incongruously lengthened, was released as a single. There were Radio Times listings, promo slots on the children’s magazine show Blue Peter, newspaper reviews, TV discussions, a press kit on Tripods-stencilled paper, a set of ViewMaster slides (covering episodes 1 to 3, and occasionally oddly captioned), and more.

BBC Video, which was only barely up and running in 1984, didn’t release the show, but technophiles could buy it as a Sony LaserDisc release instead. Condensed down to three sides — one disc double-sided, the other a single — this cinematic version had a running time of 150 minutes and was priced at $30, which is around $90 in today’s money. Not being a movie, the show had never had a movie poster, so an illustration drawing on American book jackets was used for the cover. LaserDisc was very much the cineaste’s format of its time, a home for deluxe releases of classics like Easy Rider or 2001, and not an obvious outlet for television. As with so much else about The Tripods, then, its LaserDisc release was an oddity. But despite, or because of, the abridgement of half of the running time, the BBC producers perhaps saw this as their definitive version for posterity. It was after all sold on the same shelf in shops in Tottenham Court Road as Stanley Kubrick and Alfred Hitchcock. Once again, even though editing can itself be a creative act… I’m going to say no, this isn’t a fresh adaptation.

In the twenty-first century, with the TV show forgotten, the original books have become available as Audible audiobooks, narrated by William Gaminara (an actor with no connection to the BBC production). He certainly makes some interpretive choices, and indeed, some questionable ones — he gives Will a thick country-Hampshire burr of an accent, and Ozymandias is Irish. Is that adaptation? It’s certainly the story re-presented in a different medium. But in so far as it counts, it’s too essentially similar to the original books to tell us much that’s new.

Another near miss would be the composer Ken Freeman’s music composed for the show’s hypothetical, never-made, third season: the Pool of Fire Suite.

But it cannot tell us about The White Mountains, which is two books earlier.

So what does that leave? A minute amount of fan-fic, and who knows how many unpublished drafts of never-made Hollywood movies — Disney having owned the rights for many years and never yet exercised them. Again, no.

But what I do want to look at are three other adaptations of the Tripod myth which did make it out into the open. Two of these versions are based on the TV show — which allows us for once to see it as the source and not the outcome of adaptation — and the third is completely independent.

Next: The Neverending Episode 4 ● Prev: Episode 4