Boys and Girls

Let’s move on to the two comics. One of these is interesting because it had nothing to do with the TV show, and the other because it very much did.

At the same time as the BBC was making the TV show in Europe, the books were mid-way through being serialised as a sort of graphic novel in America, in Boy’s Life. The house magazine of the Boy Scouts of America is not an obvious sci-fi periodical, but Asimov, Heinlein and Clarke have all appeared in its pages. (Heinlein’s Farmer in the Sky,[1] about boy scouts homesteading on Ganymede, is the best remembered of these works today, though the short novella A Tenderfoot in Space remains a tantalising hint of a Heinlein juvenile that might have been.[2]) Occasional yarns about a scout troop in possession of a working time machine were clearly played for comedy,[3] and it is never entirely clear how seriously to take the Space Conquerors! strip, either, which richly deserved its exclamation mark.[4]

Bookending the space age, this began publishing in the time of V-rockets and petered out with the last Apollo moon landings in 1972.

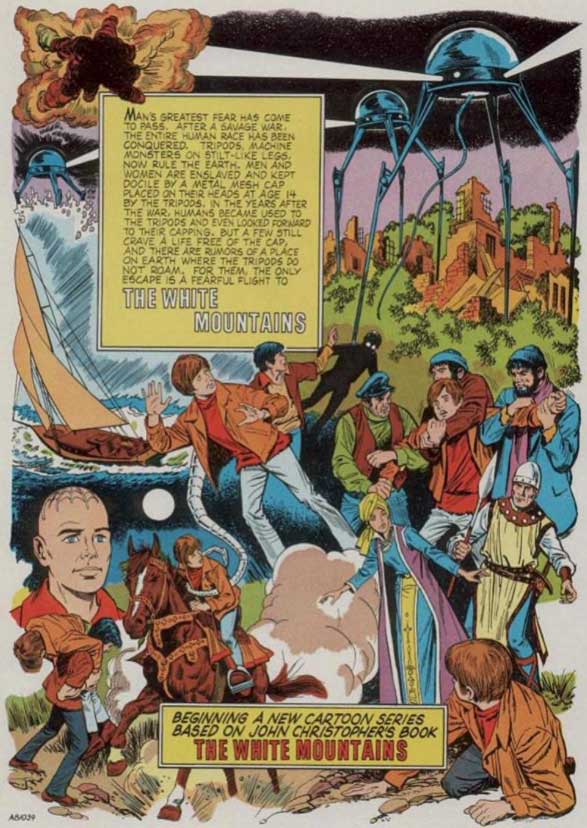

By the 1980s, Boy’s Life had mostly put aside fiction and was stylistically a men’s lifestyle magazine. Bold photographic covers showed boys skiing, mountaineering, shark-fishing or otherwise proving their mettle. Rich, white boys, a cynic might note, but growing up in the 1980s does look kind of neat. Colour printing was now being used throughout the magazine, and yet its traditional four or six page “colour section” — a sort of internal comic book — continued to appear every month. Its content had barely changed since the 1950s, and indeed would still be going in the 2000s, even as the rest of the magazine had changed around it. There were Bible stories (basically the Old Testament but with hilariously white faces), outdoor skills illustrations, true stories of escape from hiking disasters, and a funny or two for the younger kids. What the colour section had never really contained, after the demise of Space Conquerors!, was any sustained narrative story. So the May 1981 comic-book pages must have come as a real surprise: they led on the opening chapter of The White Mountains, following a bonus overture page which makes a remarkable try at painting the entire novel in one go.[5]

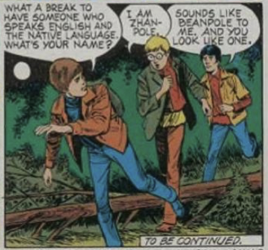

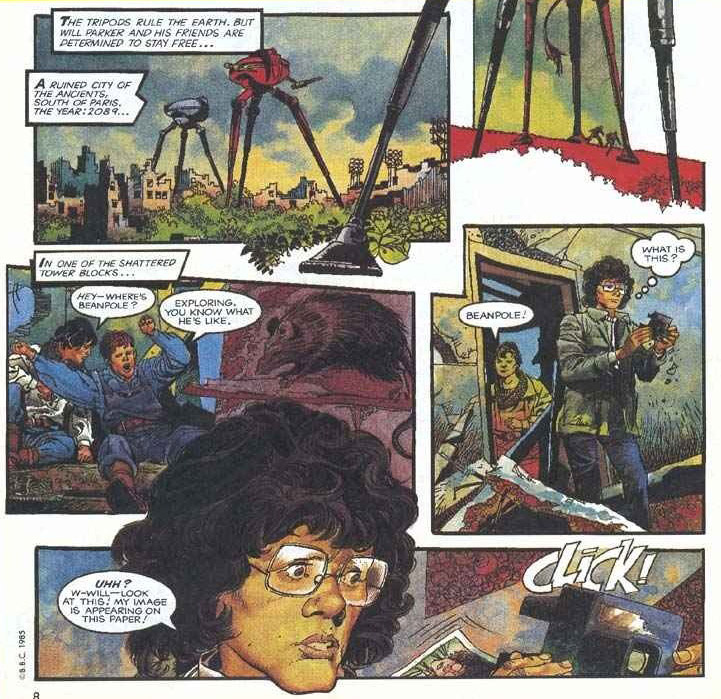

Drawn in an art style far more 60s than 80s, the Boy’s Life version of the Tripods seems at first an unambitious adaptation. But it was to run for an epic 64 instalments, which is a lot for a monthly magazine aimed at preteen boys. Most of the scouts who read the 15-part The White Mountains in 1981-82 will have developed other interests long before the 30-part The Pool of Fire ended in August 1986. The Tripods are painted in a bluish silver and the Cap is a metal spider’s web which has none of the BBC Cap’s modernity. The boys have plainly adolescent bodies, but have a good practical way of slinging packs over their shoulders, being scouts in all but name. Here’s that tricky nicknaming scene, disposed of with typical conciseness — left to right, Will, Beanpole and Henry:

Like the BBC, Boy’s Life wants to get out of Wherton as quickly as it can, and isn’t much interested in the rivalry of Henry and Will. Like the BBC, it gives Ozymandias a guest re-appearance at the end of book one. In book two, Boy’s Life excises what is, arguably, the hinge-moment of the plot: the fate of Eloise is cut entirely. Once again, the BBC thought along similar lines, in that neither adaptation was willing to say what the book says, that is, that Eloise has been humanely killed to preserve her beauty behind glass. Since the BBC never reached book three, we can’t know whether they would continue to make similar calls. But for what it’s worth, Boy’s Life plays down Julius’s reprimands to Will, who thus remains the perfect boy scout. The text is otherwise narrated faithfully, even if alcohol is always rather quaintly called GROG, and the strip even includes the collapsing peace-conference at the trilogy’s bittersweet end.

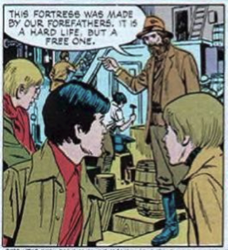

The writer, then, mostly plays it straight. The artist is more transformative, and now and then extrapolates from the book. Here are glimpses of the inside of a Tripod, and of the White Mountains base:

The artist also gives the landscape a look of sylvan wholesomeness. His mountains and rivers and woods are more High Sierras than Alpine, and his knights in armour belong to Hollywood versions of Ivanhoe more than to the middle ages. Wherton is a half-demolished small town which might once have been a prosperous spot in Oklahoma or Kansas, rather than an English rural village. A few of the free men even wear trilby hats, as if they’re film noir characters. We are not quite in Europe.

So perhaps the most instructive thing about the Boy’s Life adaptation is what it did not do: it did not take the final step of transposing the action to America. In the end I think the “Tripods” story just isn’t universal enough for that. It presents the land-mass of the European continent as one great homeland of many languages and cultures, with the high Alps at its hub. Its story of pilgrims making their way to the centre is a little like the Chinese Journey-to-the-West legend, whose heroes set off for the mountains of heaven deep at the heart of the world. Scripts for unmade movies did try to transpose the action of The White Mountains to America, but were unable to work out what the journey ought to be — should we head for the Appalachians? The Rockies? Yosemite? Along the way, what would be the cultural boundary for the American Parkers to cross, the analogue of the English Channel? French-speaking Quebec lies in the wrong direction. Would Beanpole be Pennsylvania Dutch? Or even Cherokee? A version of The Tripods where the centre of the continent has become Native American land once again would be a very different piece of writing.

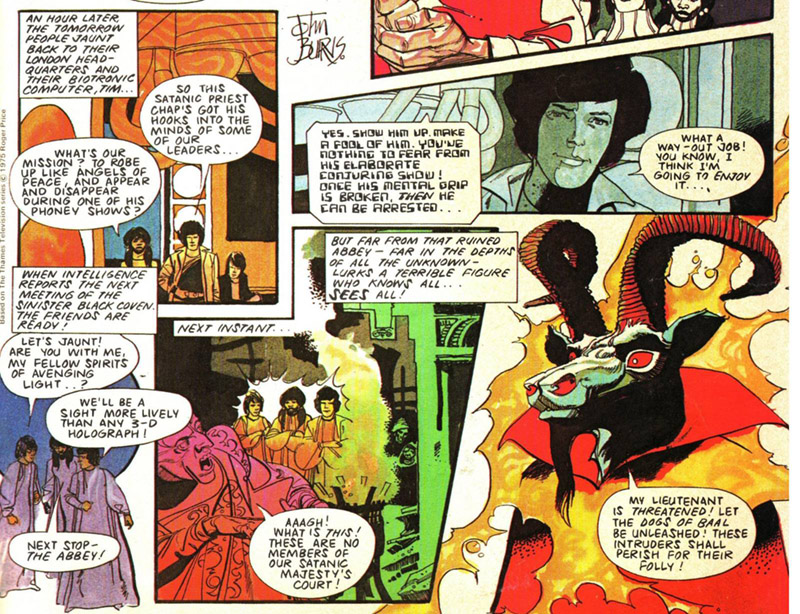

The comic strip in BEEB: The BBC Junior Television Magazine is so different from the one in Boy’s Life that it’s hard to believe the two were simultaneous. Launching on 29 January 1985, a month after series 1 had broadcast its finale, BEEB was — like its venerable commercial television rival Look-In — a hybrid of comic strips and pop music articles. The Tripods and the school-based soap opera Grange Hill were its leading cartoons, allocated three pages each per issue. This was not a new idea. Telefantasy shows of the 1970s had routinely had comic-strip spin-offs like these: Timeslip, Space: 1999, Sapphire and Steel and Doctor Who, among others, all had subsidiary adventures in magazines sold to children in newsagents, and in Christmas-present hardback “annuals”. Here’s a 1975 frame of The Tomorrow People, whose “biotronic computer”, Tim, speaks in the Westminster font, which had been designed in 1965 for better optical character recognition on cheques presented to the National Westminster Bank.

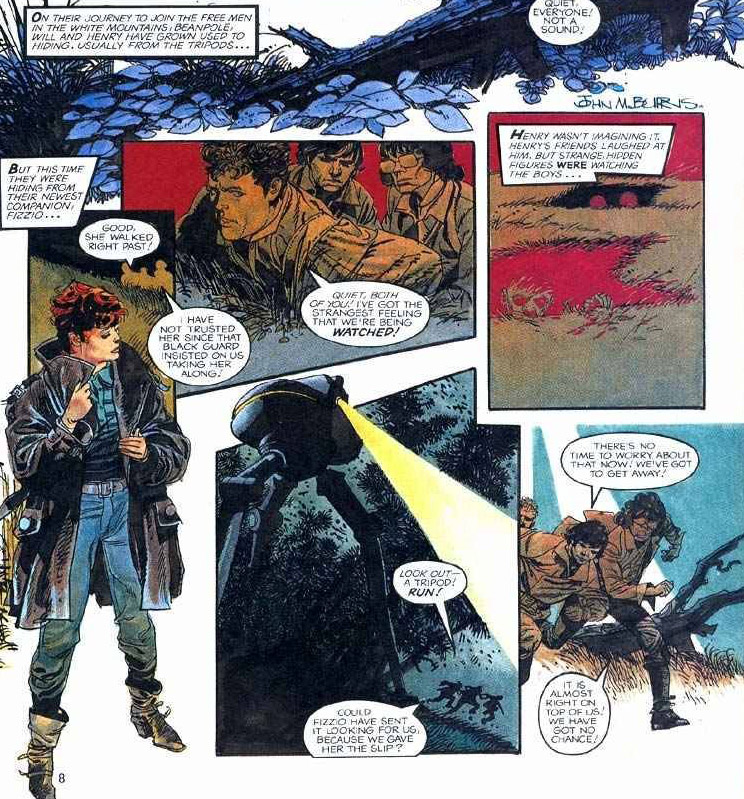

Despite running in comics, these strips were pitched at a serious-minded level — in the case of The Tomorrow People, generally more so than the show they depicted — and the standard format was to run six to eight week serials, one serial after another, until children had moved on to a different enthusiasm. What gives these different shows a certain unity of style and design on the page is that they were very often drawn by the same veteran artist, John M. Burns.[6] As had been true back to the formative days of Dan Dare in the Eagle, colour printing was expensive, so it had to be reserved for prestige pages only. A week’s ration of The Tripods, for example, gave you two colour pages and one monochrome. That now makes reading the strip in album form slightly odd, since every third page is in black and white and, moreover, drawn stylistically differently to accommodate that. But you get over this surprisingly quickly.

The BEEB comic strip is more lushly drawn and inked than the Boy’s Life one, with page designs which are also considerably more dynamic and irregular. The influence of French BD is clearly visible in Burns’s work, but even if he did not invent these layout ideas, he nevertheless carries them out with enormous assurance, especially in the grammar used for unexpected sound or movement. Note the disruptive way in which motion and surprise overflow the frames.

However, since the strip closely follows the look of the TV show, it doesn’t get to make many visual choices, so we’ll look more at the writing. This consists of six untelevised adventures, none even loosely taken from the books. The opening story is set in “A Ruined City of the Ancients, South of Paris”, which in theory places us in some narrative crevice in episode 8, but the opening page — a vignette of Beanpole discovering a working Polaroid camera — seems once again very indebted to episode 4. And Will, it may be noted, is still wearing his string scarf from Wherton, which on television becomes steadily more bedraggled until, one assumes, the Countess Ricordeau has it burnt while he’s unconscious between episodes 4 and 5.

As in the computer game, roaming through a deserted France will be the milieu throughout. No sooner have we established our characters than we enter a world-turned-upside-down tale about football hooliganism, told with a satirical violence vaguely recalling 2000 AD comic. (That turns out to be a one-off, though, and remaining story-lines feel closer to the mood of the show.) There are some great panels of Beanpole climbing among the steel gantries of the stadium, and of the titular Tripods, who are freed of their limited special-effects budget and can run amok. At least some of the Capped can communicate with Tripods at least some of the time — something never actually shown on television. We also have two new characters. “Fizzio”, the physiotherapist, may or may not be another runaway. The boys do not trust her but the other new character, a Black Guard who claims to be a member of the resistance, instructs them to take Fizzio to the White Mountains. The second tale takes what is now a quartet to an underground village in a former coal mine; the third features an attack on a further ruined city where trigger-happy Tripods trap Beanpole in the rubble of an abandoned library. Story 4 features a storm and a witch’s cottage — the latter plot, an attempt to give Fizzio something to do, is more or less out of the Brothers Grimm. Story 5 takes us to something only briefly present in the novel and never even attempted on screen: Lake Geneva. If that fits anywhere, it is an out-take from episode 11. An evocatively drawn story, it flows straight into the sixth and last, which features a deluded man who believes the Tripods have made him a King… and who is never disillusioned because BEEB magazine then folds, taking all of its strips down with it, this one included. “There is nothing we can do, Fizzio!” says Beanpole in the final frame ever. “This is the end, for all of us!” Though The Tripods has never been published in album form, and probably can’t be for rights reasons, a compilation does circulate online. Somebody must have cared enough to preserve it, and — as with the consolidated Boy’s Life run — the result is a pleasing volume on roughly the scale of a Tintin book.

What can we learn about the Tripod-myth from BEEB comic? One uncomfortable lesson is that it’s not all that easy to come up with new tales about our gang. The source is a plot-driven novel with a finite story, not a series bible for endless adventures. All that our heroes can do is wander from one eccentric community to another — the BBC drama Survivors often had the same predicament finding things to do in its own post-apocalyptic world. In particular, having not yet joined up with the Free Men, our heroes can’t be given Resistance-related tasks to perform. It would have been much more fruitful to exploit the period between series 1 and 2, and have our heroes sent out on espionage missions by Julius, or something of the sort.

That would also have made it easier to introduce the female team member. Fizzio’s existence in these stories is one long contradiction of both the show and the book. Her arrival moment vaguely imitates Beanpole’s, and she too gets a daft phonetically-misheard name. But in narrative terms she absolutely does not fit. Are we to suppose that the boys find and then ditch a woman in some way so shameful that they never speak of it in their broadcast adventures? Drawn as older than the boys, perhaps to make her more of an aunt-figure than a potential girlfriend, Fizzio seems to be a mature woman: so why is she, the only adult in the room, letting teenagers make all the decisions? The strip has some trouble in preserving Will as what Henry, at one point, calls “our unofficial leader”. Her addition to the scenario is a truly drastic change.

So why was Fizzio added to the BEEB adaptation? The answer, of course, is that The White Mountains is a book almost exclusively for and about boys. That suited Boy’s Life magazine down to the ground. If anything the story was made more male in their pages, not less: Will’s mother and the Countess appeared in only one frame each, and its Free Men were exactly that — men. BEEB, on the other hand, wanted female readers as well, and we have to suppose that the TV show did too. So the question we should really be asking is not why BEEB adds a female team member, but why the TV show doesn’t. It flirts briefly with two girls as potential recruits but neither comes on board. Although the Free Men appearing in the last minutes of series 1 and in series 2 include plenty of young women, they have frustratingly few lines and are swiftly disposed of, for no very good reason. And so The Tripods remains very much a male-dominated show. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to the BBC to make any of the five lead freedom-fighters (Will, Henry, Beanpole, Fritz, Julius) female — to turn Henry into Henrietta, say. That may be the most dated thing about The Tripods today.

But it’s time to unplug the Spectrum from the TV’s aerial socket, and to put away BEEB magazine, with their endless attempts to prolong episode 4. It’s time to visit a castle, where the story will develop completely differently, and where Eloise — our one female character of real substance — will appear at last.

Works cited:

- Farmer in the Sky (1950), by Robert A. Heinlein, though it had been called Satellite Scout in the August, September, October, and November 1950 issues of Boy’s Life, rather suggesting that RAH hadn’t been sure how far he was taking the story. Wikipedia

- A Tenderfoot in Space (1958), by Robert A. Heinlein, running in the May, June, and July 1958 issues of Boy’s Life. It has since been republished in an unabridged form, but a novel it will never be. Wikipedia

- These were the “Polaris Patrol” stories by Donald and Keith Monroe, mainly belonging to the 1960s: they were eventually anthologised into book form. Wikipedia.

- For the complete meandering run, see the Internet Archive compilation of Space Conquerors! here.

- Boy’s Life has been systematically archived by Google Books, and the Tripods strip in particular is once again compiled at the Internet Archive.

- For the work of John M. Burns, which also ranged from graphic novels of Wuthering Heights and Jane Eyre right through to girly strips for tabloid newspapers, see Wikipedia. Tripods was his final old-school telefantasy strip, and also his main narrative work of 1985.

Next: Introduction to Part II ● Prev: Entr’acte — The Neverending Episode 4